Introduction

Welcome to Women, Worded. This digital project explores how the narrative surrounding women at Washington and Lee University has evolved over time (from the 1960s until the 2000s) with an emphasis on the period when the institution transitioned to coeducation (mid-1980s). The project uses quantitative and qualitative text analysis to look at what language students, faculty, alumni, and the administration have used to refer to women throughout time in the school newspaper, as well as in private letters and correspondences pertaining to coeducation. The project culminates in a timeline that connects those narratives and sentiments to larger events associated with the feminist movement in the United States.

Context on a national scale

Liberal arts colleges across the United States over time have had differing views and approaches to integrating women into their student body, as for the longest time college was mostly the domain of men. Due to reasons such as the adherence to tradition and the supposedly superior performance of men in academics, men remained at the forefront of the higher education battlefield until at least the 1960s. In her article Expansion and Exclusion: A History of Women in American Higher Education, Patricia Albjerg Graham writes that, “unlike men, who were never barred from attending college on account of their sex, women were unable to enroll in any college until Oberlin permitted them entrance in 1837, ostensibly to provide ministers with intelligent, cultivated, and thoroughly schooled wives.” (Graham, 1978) Even after women began getting admitted to certain universities, preference in admissions was often given to men. If admitted, women had to face additional challenges such as special curfews and regulations (Goldin and Katz, 2011). Despite the social and legal barriers, women came to make 21 percent of the total undergraduate enrollment in the country by 1870. This figure included the students in the newly established women's colleges that began to sprout up and down the east coast as independent schools. By 1880, women constituted 32 percent of the undergraduate student body. A decade later, in the 1920s, women were 47 percent of the undergraduate enrollment, nearly as much as their proportion in the population (Graham, 1978). Today, women receive 57 percent of all BAs in the United States (Goldin and Katz, 2011).

Coeducation at Washington and Lee

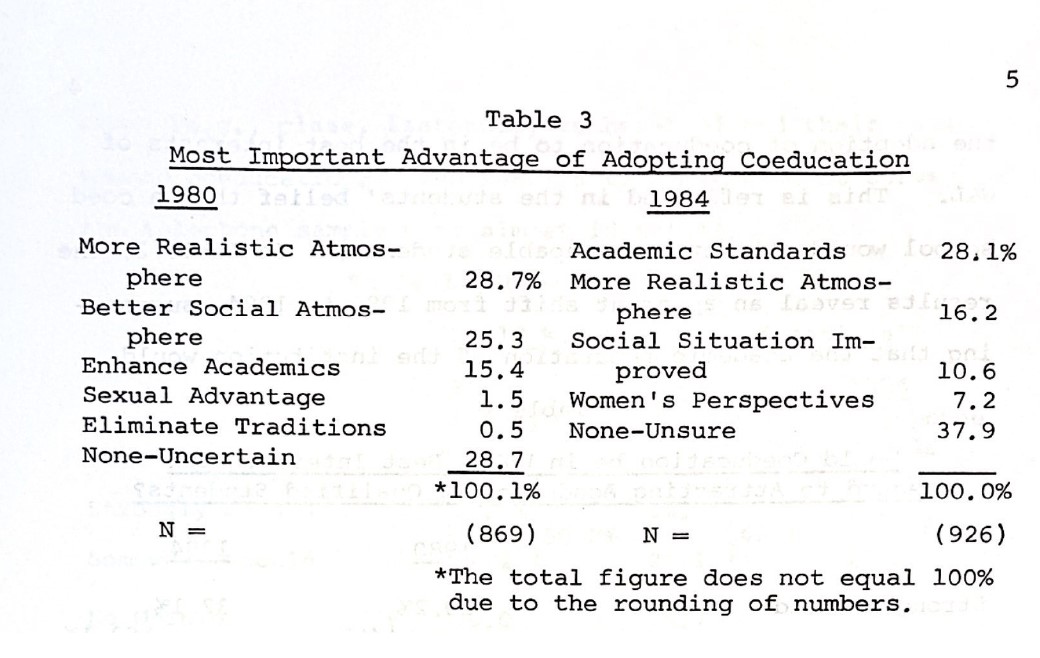

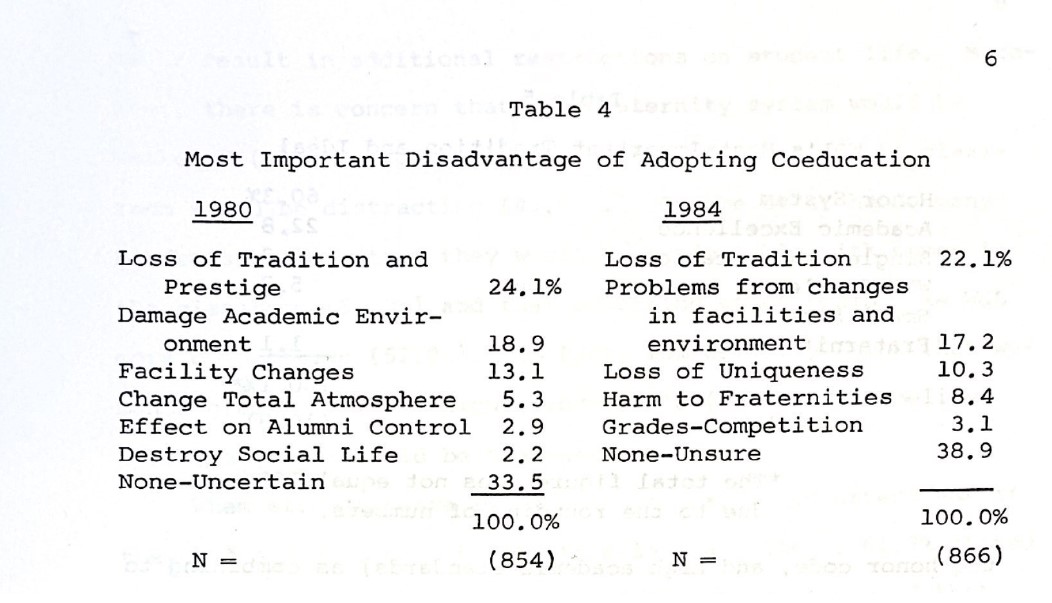

At Washington and Lee University, the first undergraduate women matriculated as late as 1985, making it one of the last liberal arts colleges to accept women. One might call it a late bloomer. In fact, it was one of only five remaining all-male schools in the country (Canaan, 2013-2014), and one of only three nonmilitary ones, along with Hampden-Sydney College and Wabash College in Indiana (Brownell, 2017). Admitting women undergraduates had been studied twice before between 1969 and 1975, but without notable controversy or final resolution. However, when the issue was taken up for review again in October 1983, it generated far more debate and especially strong opinions among alumni and friends of the university. A poll revealed the majority of students opposed to coeducation, but faculty members were strongly in favor (Brownell, 2017). According to a 1980 student survey and a 1981 faculty survey on coeducation, the most important advantages to coeducation were “academic standards” and a “more realistic atmosphere.” (Novack, 2013) The respective disadvantages were a “loss of tradition and prestige” and problems arising from changes in the facilities and academic environment (Novack, 2013). The university announced that it would begin to admit female students on July 14, 1984, after two days of meetings with the Board of Trustees. The decision came down to a vote, with 17 members approving of coeducation and 7 disapproving. President John Wilson announced that up to 100 female students would be admitted in the fall of 1985, but 105 were actually admitted (Brownell, 2017). Despite the passing of the decision, the transition to coeducation at Washington and Lee was anything but smooth and seamless. Students protested, and alumni bombarded the then-President John Wilson with letters of disagreement. Due to the university’s long all-male history and strong ties to tradition, the transition of women was especially difficult and they proceeded to face animosity for years to come.

A framework for understanding gendered language

In order to better understand the struggles women at Washington and Lee have faced and still face, we need to understand the feelings and attitudes toward women that students, faculty, and staff have shared, and how those might have evolved over time. In this project, I decided to examine the narratives about women that have been established, as reflected in the language that has been used to refer to them over time, and specifically the use of gendered language and nouns. “The relation between language and thought is bidirectional and reciprocally causal; each shapes the other in ways that are consequential for human behavior,” write Rebecca Bigler and Campbell Leaper in Gendered Language: Psychological Principles, Evolving Practices, and Inclusive Policies. The notion that language influences gender-related cognition, affect, and behavior is decades old and well supported by research (Bigler and Campbell, 2015). According to an article from the Journal of Language and Social Psychology, the words “woman” and “female”, as well as their respective plural forms, are seen as more neutral ways to refer to women, while the words “lady” and “girl” have been seen as sexist, biased, imprecise, and diminishing. What’s more, terms such as “lady” and “girl” connote images of women that are “consistent with stereotypic domains of high warmth and low dominance.” (Cralley and Ruscher, 2005) Both men and women vary in how strongly they associate women with these domains, and the strengths of these associations can be implicit (i.e., relatively subconscious), or explicit. Even though there are circumstances in which “lady” and “girl” might seem precise and appropriate, when it comes to day-to-day written communication, professional organizations view those terms as gender biased. Overall, gendered language matters and can be very telling when it comes to understanding both explicit and implicit attitudes and biases. In this case, the very attitudes that affected Washington and Lee’s decision to admit women, as well as the way they were regarded and treated later.

Why text analysis?

This project uses text analysis. I believe text analysis is an appropriate method to apply here, since it can shine light on some important correlations between language, attitudes, and decision-making only visible on a micro-level. Text analysis is defined as “any systematic reduction of a flow of text (or other symbols) to a standard set of statistically manipulable symbols representing the presence, the intensity, or the frequency of some characteristics relevant to social science,” and it includes both qualitative and quantitative approaches (Mehl, 2006). It is often used for “sentiment analysis,” which encompasses detecting, analyzing, and evaluating humans’ state of mind toward different events, issues, services, or any other interest. More specifically, “this field aims to mine opinions, sentiments, and emotions based on observations of people’s actions that can be captured using their writings, facial expressions, speech, music, movements, and so on.” (Yadollahi, Ali et al., 2017) For this project, I performed a type of sentiment analysis that uses both quantitative and qualitative text analysis techniques in order to examine the narratives surrounding women at Washington and Lee University over time, and how those might be reflective of how women were treated before and after the university decided to go co-ed.

Bibliography

Bigler, Rebecca S., and Leaper, Campbell. "Gendered language: Psychological principles, evolving practices, and inclusive policies." Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2.1 (2015): 187-194.

Bowen, David Charles. "Coeducation at Washington and Lee University: a Social Systems Approach." 2013. Record Group 38, Washington and Lee Special Collections.

Brownell, Blaine A. "Washington and Lee University, 1930-2000: Tradition and Transformation." Louisiana State University Press, 2017.

Canaan, Ashley Reed. "Better Dead Than Coed: the Coeducation Debates at Washington and Lee University." Maggie L. Walker Governor's School for Government & International Studies, 2014. LD5873 .C3 2013, Washington and Lee Special Collections - Rare.

Cralley, E. L., and Ruscher, J. B. "Lady, Girl, Female, or Woman: Sexism and Cognitive Busyness Predict Use of Gender-Biased Nouns." Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 24(3), 300–314. Sept. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X05278391

Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz. "Putting the “co” in education: timing, reasons, and consequences of college coeducation from 1835 to the present." Journal of Human Capital 5.4 (2011): 377-417.

Graham, Patricia Albjerg. "Expansion and Exclusion: A History of Women in American Higher Education." Signs, vol. 3, no. 4, 1978, pp. 759–73. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173112.

Head, Tom. “Feminism in America from 1792 through the Millennium.” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 24 Oct. 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/feminism-in-the-united-states-721310.

Mehl, M. R. Quantitative Text Analysis. In M. Eid & E. Diener (Eds.), Handbook of multimethod measurement in psychology (pp. 141–156). 2006. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11383-011

Milligan, Susan. “Timeline: The Women's Rights Movement in the U.S. .” U.S. News & World Report, U.S. News & World Report L.P., 10 Mar. 2023, https://www.usnews.com/news/the-report/articles/2017-01-20/timeline-the-womens-rights-movement-in-the-us.

Nicoletti, Leonardo, and Sahiti Sarva. “When Women Make Headlines.” The Pudding, The Pudding, Feb. 2022, https://pudding.cool/2022/02/women-in-headlines/.

Novack, David R. "Coeducation at Washington and Lee University: Student and Faculty Perspectives." 2013. Faculty Publications, Washington and Lee Special Collections.

Simpson, John et al. "Text Mining Tools in the Humanities: An Analysis Framework." Journal of Digital Humanities, 17 July 2013, http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/2-3/text-mining-tools-in-the-humanities-an-analysis-framework/.

Yadollahi, Ali et al. "Current State of Text Sentiment Analysis from Opinion to Emotion Mining." ACM Computing Surveys 50, 2, Article 25 (March 2018), 33 pages. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1145/3057270.